Avid S7?

At the time of writing, Avid’s S6 control surface is just over eight years old.

Launched in 2013, S6 replaced the Icon range, when Icon D Command was eight years old. There’s nothing to suggest the tempo will be similar this time around, no rumours of Avid’s future control surfaces on the horizon. No whispers of Avid S7.

The past eight years has seen the advent of immersive formats (or rather, the ability to monetise working in them), the continued march towards infinite track count, and more recently a need to reevaluate where and how mixing work is done. There’s an audience for innovation.

So where is the next-gen future control surface coming from, and when? It seems unlikely that Avid has anything significant in-the-works, and there’s a good reason why.

Not all dollars are worth a dollar

Over the past year or two Avid’s stock price has soared. Not because Avid is killing it with revolutionary new products or attracting waves of previously un-tapped new customers. It’s not. There’s another reason, and it has to do with the nature of its revenue, and the type of products Avid are selling.

Avid’s revenues overall have been declining over the past decade, but that’s not necessarily an issue for investors. Investors want to see the right kind of revenue. Software subscriptions, for example, are regular, predictable and don’t require costly face-to-face interactions. Shareholders also love Support Contracts and Enterprise Agreements, whereby large Avid customers (end users and resellers) have contractually committed to a defined annual spend. The money investors want to see is money that’s definitely coming, set this against falling costs, and this positive sentiment appears to be priced into Avid stock.

This ‘right kind of revenue’ accounted for around 70% of Avid’s sales so far in 2021, with management telling investors that 80% is the goal by 2025.

At the same time, profitability of products sold is on the rise. A cloud-based software license, or a renewed support contract, has negligible material cost. Conversely, state of the art mixing consoles carry high manufacturing cost. Selling mixing desks has the unfortunate side effect of dragging average gross margin down. Investors don’t like that.

Question (well, loaded rhetorical question): If you were the management of a transformed Avid, seeing the company in profit and with stock prices tickling 40 dollars, would you invest in developing and selling a complex hardware product which is expensive to manufacture, and which will work for many years with no built-in rebuying cycle?

This is not a criticism, Avid is flying. Neither is it a dirty corporate secret, it’s a success story. CEO Jeff Rosica, when reviewing the goals set by Avid’s management team, told investors:

We see Avid being a predominately software, subscription, and SaaS company by 2025, if not sooner

Avid CEO Jeff Rosica, May 2021

What does this tell us about next-gen consoles?

Avid’s lack of appetite for future control surface R&D is understandable. It is also evidenced by recent releases, which are either an increment on existing technology (S1, S4, Carbon, Sync X) or re-badged 3rd party products (MTRX, Sonnet Chassis).

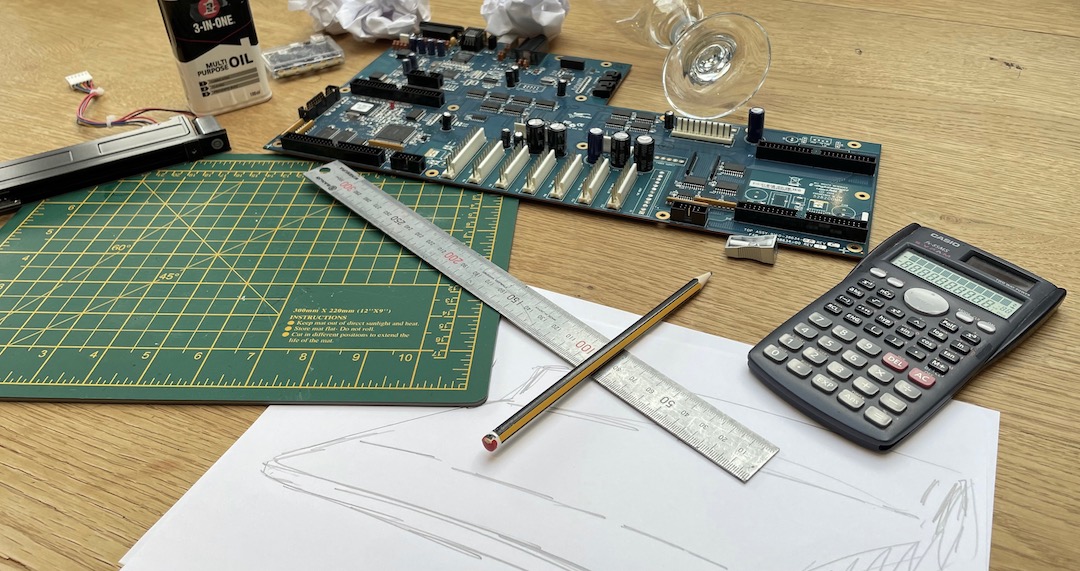

Looking more closely at S4, created to replace the S6|M10 range, we see a new product which shares a high proportion of components with the model it replaces. Where it differs is a simplified channel module and the (all-important) faders which feel different. Not better or worse, just different. Oh who are we kidding – customers tell us they feel cheap. For good reason.

S4 exists because S6|M10 was too expensive to justify making, relative to its customer price point. S4 is cheaper to manufacture than S6|M10 and required only modest R&D investment. Meanwhile, channel-for-channel (at around $55k for a 24 fader S4) it’s not any cheaper for the customer to buy, giving it a better profit profile for Avid.

Where is the next new console coming from?

It’s tempting to conclude that it’s probably not from Avid.

Avid is focussed on the value of its software IP – and rightly so. These are the guys who make Pro Tools, Media Composer and Sibelius after all. Following the acquisition of Euphonix in 2010, they’re also the guys who make EUCON.

The EUCON SDK has been open to 3rd party software developers, even rival DAWs, from the outset. If a Nuendo, Pyramix or Logic Pro user has opted away from Pro Tools – then OK, at least they can still be an Avid control surface customer.

Importantly, EUCON has never been open to 3rd party hardware developers. Many in the film world would have loved to see their AMS DFC consoles getting deep, intuitive control of Pro Tools, but (conveniently ignoring the technicalities) that’s never been how EUCON works as a commercial proposition.

Right, then. Now. Bold type and underline engaged: For the avoidance of doubt, we’re not saying this is what’s going to happen – but – it would seem to make sense – and be strategically consistent – for today’s financially healthy, and tomorrow’s “predominantly software” Avid to licence EUCON to 3rd party hardware manufacturers for future control surfaces.

Avid would pass the R&D and manufacturing cost to 3rd parties. In return, those hardware-focussed companies could develop first-class, deeply-integrated Pro Tools, Nuendo, Pyramix and Logic Pro control surfaces. Over time, these products will gain new functionality with each new EUCON release.

Sure, Avid would lose the revenue and margin from selling their own control surface products, but does it matter? At this stage in the S6 product life cycle, a high proportion of users have bought all the S6 consoles they’re likely ever to need. The only way to extract any future console revenue from those customers will require Avid to invest years and millions inventing something new to sell them.

Given it’s the wrong kind of revenue anyway, with a below-average profit contribution – Is it worth it?

Some lost revenue would be offset by licensing royalties from the 3rd Parties who develop EUCON hardware products, and from annual subscriptions. Here, once again, is the right kind of revenue.

Yamaha, SSL, AMS Neve, Focusrite, Blackmagic Design – just a few examples of companies who are great at making stuff. Yamaha (Steinberg) and Blackmagic (Fairlight) might provoke a competitive red flag, but in the spirit of co-opetition, where’s the harm?

Certainly the customer, and the craft of mixing, stand to benefit.